Alumna’s medical career spans hospitals, Army bases and state institutions

Adadot Hayes focuses her work on helping people with neurodevelopmental disabilities, such as cerebral palsy and Down syndrome.

More news

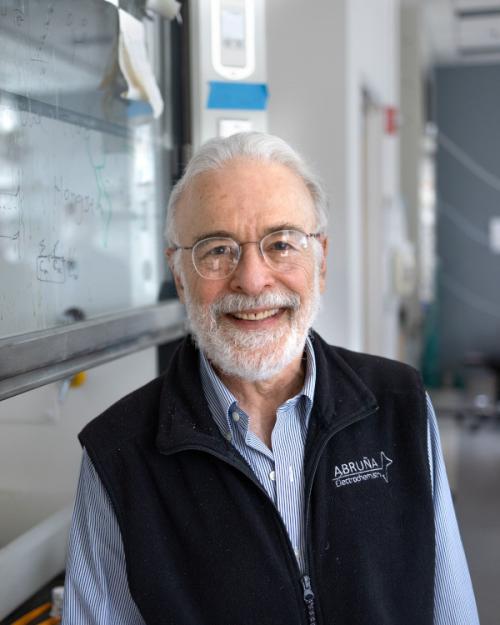

Abruña honored for chemistry in the public interest

A&S Communications

Student spotlight: Bayu Ahmad

Cornell University Graduate School